(Bishop of Lipari from 1778 to 1789)

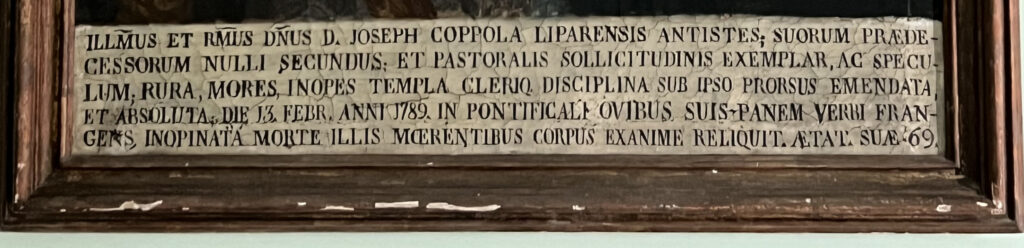

The bishop is portrayed seated with his left hand resting on a large Bible, behind which the episcopal insignia can be discerned. The inscription at the bottom also recalls his sudden death that came as a result of an apoplexy that struck him while “breaking the bread of the Word to his sheep” during the Pontifical on Feb. 13, 1789.

Bishop Coppola, who was of Palermo origin, was a character of great charisma and rich interests. In addition to devoting himself to the training of clergy, given the “deplorable situation of the damsels,” he invested a great deal in the moral education of young girls, bringing in teachers from Sicily who were to teach “the fear of God, sensitivity to good morals, Catechism and women’s work.” Also in this direction, a major work he set his hand to was the construction of a magnificent building, near the bishop’s palace in the village, dedicated to orphans, educande and those who voluntarily “want to withdraw from bad manners“. Another building Coppola built was the women’s hospital of the Annunziata, which took over the name of the small hospital at the Castello, now inadequate and run-down.

He also favored with numerous interventions the development of agriculture and to obviate the problem of water shortage, he attended to the construction of three large cisterns: two in front of the great gate of the bishop’s palace and the other in front of the Church of the Rosary.

Culture was also part of this bishop’s social program and so, in 1782, he moved the Seminary of Letters to the enclosure of the bishop’s palace, which he wanted open to the public, as well as his library. He also created an antiquarium where he collected various archaeological artifacts that he had found in the excavations done to make the classrooms of the Seminary of Letters. His attention also turned, of course, to the restoration of the churches; in the Cathedral, in particular, he gave the finishing touches after the extension work, also having the large altarpieces of the side altars, which still exist today, made by the Palermo painter Antonio Mercurio.

He garnered the appreciation of Lazzaro Spallanzani, who got to know him during his trip to the Aeolian Islands.